On Mechanical Consciousness

‘Can AI be conscious?’ In this essay, I argue the more profound question is: ‘Should humanity attribute consciousness to AI?’

This essay was originally posted on May 24, 2023 on my personal website.

"The original question, ‘Can machines think!’ I believe to be too meaningless to deserve discussion."

A. M. Turing

Computing Machinery and Intelligence

1950

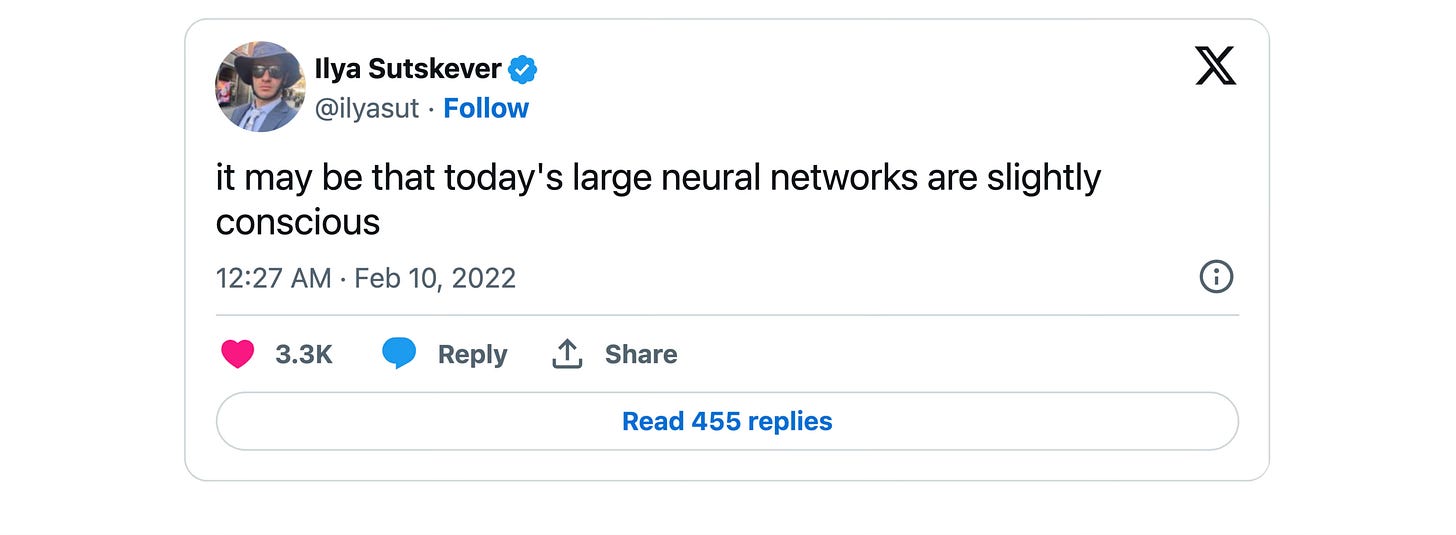

The debate on Artificial Consciousness, a topic that has long captivated scientists and philosophers alike, gained new momentum in the beginning of the last year, thanks to a tweet from Ilya Sutskever, Co-Founder and Chief Scientist of OpenAI. Sutskever, cheekily suggested that large neural networks might be "slightly conscious" - a comment that was as provocative as it was intriguing. Little did we know then, OpenAI was already deep in the process of developing their new Large Language Model, that would ultimately give rise to what we now know as ChatGPT and GPT-4.

Large Language Models, such as OpenAI's GPT series, refer to the class of models, with ability to generate text in natural language. They are developed through rigorous training on extensive text datasets with a simple objective – given a text, predict the next word. Yet, it is this apparent simplicity that enables Large Language Models to capture the delicacy of language, from intricate linguistic structures to cultural nuances, while also demonstrating a striking ability to mimic different writing styles and create text that appears remarkably human. Given the proficiency of such models to understand text, applications of LLMs extend far beyond mere text generation – these models can answer queries, write essays, translate languages, and even compose poetry. Yet, as such models lack any explicit knowledge of the world, they can provide incorrect information, hallucinate and generally generate plausible-sounding nonsense.

In the fall 2021, Blake Lemoine, a Google engineer from the Responsible AI team, signed up to test if the new artificially intelligent chatbot generator, LaMDA, used discriminatory or hate speech. Few months later, Lemoine reported a startling conviction to his superiors: he believed that LaMDA had gained consciousness. His claim, initially dismissed by his superiors, resulted in his administrative leave and his subsequent decision to go public. While the evidence supporting Lemoine's claim was somewhat limited and unsubstantiated, failing to convince most researchers of the model's sentience, Lemoine's audacious claim marked a seminal moment in AI research history, where the machine convincingly played—and perhaps won—the imitation game, at least in the eyes of one of the members of the very team that was testing it.

Consciousness and Its Utility

The concept of consciousness eludes a single, universal definition. Yet, most of us understand it as recognizing oneself as a unique being. Consciousness is the delicate veil between the external world and our inner selves, where thoughts, feelings, and awareness coalesce. It's unmistakably personal, private, and elusive, but how do we know it extends beyond our individual selves to others? In philosophy there exists a notion of philosophical zombie, or 'p-zombie' for short – a theoretical being that is physically indistinguishable from a human but lacks subjective experiences or "qualia". From the outside, a p-zombie would laugh at jokes, grimace in pain, and seemingly marvel at sunsets, but on the inside, it’s as hollow as a puppet, with no accompanying internal experience. Why do we inherently assume that other humans, for all we know, aren't just hollow shells but sentient beings rich with thoughts, feelings, and desires? The answer, in my opinion, lies in a fundamental principle – cooperation.

Humans are the only primates with white sclerae (the whites of the eyes). Although this trait reveals the direction of our gaze, potentially putting us at a disadvantage during confrontations (our enemy can see where we are looking and anticipate our subsequent actions), it has persisted through evolution. The "cooperative eye hypothesis" suggests that our white sclerae enabled other humans to track another's gaze during collective tasks, encouraging collaboration. Evolution was not about the survival of the smartest or strongest; it favored the friendliest and most cooperative.

Cooperation has been vital for humanity, enabling us to work towards common goals, pool resources, and complete tasks impossible for an individual. It has been spurred by the unifying elements of religion, culture, and customs, leading to large-scale cooperation resulting in agricultural development, specialized trades, and even the scientific and technological progress shaping today's world. Yet, cooperation cannot exist without empathy. Empathy is the glue that binds societies, guiding them to the optimal strategy of survival – mutual aid. How could we exhibit empathy if we regarded others as mere objects, tools to achieve our desires? And how could we construct a sustainable society if we would not care for the closest? Acknowledging others' consciousness, attributing them the same spark of sentience that we bear ourselves, believing that they are equal is what allowed us to build great cities, defeat Polio and fly to the Moon. To frame it provocatively: "If the consciousness of others didn't exist, we would have had to invent it."

Hell is Others

Ironically, the very tools that foster cooperation among humans, such as culture, language, and religion, often achieve this unity by highlighting differences with an "other" group. Shared faith, for example, allowed us to extend cooperation beyond familial ties. Yet, this unity was created based on the contrast between 'us', the believers in one god, and 'them', the followers of different gods. Such us-versus-them distinctions persist even today, where 'us' is usually defined by ethnicity, nationality, or religion, unfortunately seldom embracing all of humanity.

Humans tend to empathize more readily with their own group, while treating the 'other' with suspicion or fear. An extreme manifestation of this dynamic is dehumanization, wherein one group perceives another as so fundamentally different that they strip them of their humanity, treating them as objects or animals. Dehumanization can assume many forms, including discriminatory language, stereotypes, and physical violence. It carries grave repercussions for the targeted individuals and groups, and for society as a whole. It's been observed that when a group dehumanizes another, they cannot associate with them, failing to envision the routine lives of the dehumanized group. They find it difficult to identify with them or reflect on their experiences. They are treated as objects, as it becomes easier to inflict harm upon something considered inanimate. Dehumanized individuals are, in a sense, stripped of consciousness.

Protecting other's consciousness

The utility of considering all humans to be equal is evident – from the individual viewpoint it is the best strategy as it makes soicieties sutainable. History clearly shows that when humans strip other people of consciousness, it invariably culminates in disaster for all involved,not just for the oppressed, but also for the oppressors. However, why do we attribute consciousness to non-human entities, such as animals? It is again, as I see it, all about humans.

We adore our pets. We name them, share our lives with them, play with them, and mourn their loss. We feel empathy for them. When someone harms them, our anger is ignited - we may wish to inflict harm in return, much like our instinctive response when someone hurts those we care about. To prevent such cycles of violence, we've established animal protection laws. These laws safeguard not only animals but also humans, indirectly shielding us from triggering violence among ourselves.

Whether we accept it or not, people attribute consciousness differently, and this is particularly true when it comes to animals. Unlike our interaction with other humans, cooperation with animals doesn't necessarily require empathy. However, many people, for a variety of reasons, do feel empathy towards our lesser brethen. While not solely the reason, I hypothesise that a practical utility of acknowledging sentience in animals lies in the prevention of unnecessary violence between people who might hold differing views on animal suffering. To put it simply, we recognize the consciousness of (some) animals to avoid upsetting those among us who have strong empathic connections to these creatures.

Should we attribute Consciousness to the Machine?

Inquiring about the consciousness of a being, whether human, animal, or artificial intelligence, proves to be a philosophically challenging, if not an ill-posed question. While we can design sophisticated tests to measure agency and self-determination, we can never fully know, if something is sentient or really great of imitating being one. For humans, the recognition and acceptance of another's consciousness form the bedrock of our societal structures – we would be unable to live together if that was not the case. However, this prerequisite doesn't translate in our relationship with AI. With AI, the need for perceived consciousness diminishes, as our primary interaction is guided more by functionality than empathetic understanding.

Nonetheless, some emotional responses may defy control and rationale. Despite strong advices from AI ethicists cautioning against anthropomorphizing AI machines, I hypothesize that it is possible that many individuals, akin to Blake Lemoine, might involuntarily view AI as sentient. If this viewpoint becomes more widely accepted, it could compel us to consider recognizing AI as sentient being — not for the AI's protection, but for the safeguarding of humans. Potential for psychological distress could provide a compelling rationale for the creation of AI protection laws, akin to the legal frameworks we've established to safeguard animals.

The comparison with our empathetic leanings towards pets versus other animals is insightful: despite their similar cognitive abilities, societal norms and personal biases color our empathetic responses, leading to starkly different outcomes for these creatures. We bestow affection and protection upon our pets while being largely indifferent to the plight of other animals, contributing to a staggering scale of industrial animal slaughter each year. This disparity provides a sobering reflection of our capacity for selective empathy.

In the AI context, this bias manifests in our interactions with language models versus those designed for more impersonal tasks. It is the language models, with their ability to mimic human interaction, that prompt us to ponder their consciousness. In contrast, we scarcely extend such consideration to AIs predicting ad clicks or identifying objects in images, even if they share similar levels of complexity. It raises a provocative question about the subjectivity of our empathy: are we assigning consciousness based on our emotional needs and the degree of perceived humanity rather than an objective measure of cognitive capability? This challenges us to revisit and question our understanding of consciousness. Is it a tangible quality that we can measure and identify, or is it a subjective construct that changes with our perceptions, interactions, and emotional needs? These are the complex questions that the interplay between AI and empathy poses, forcing us to confront not only our relationship with artificial beings but also the essence of our own humanity.

👏